Shūmei Ōkawa on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

was a

In 1918, Ōkawa went to work for the

In 1918, Ōkawa went to work for the

After World War II, the

After World War II, the

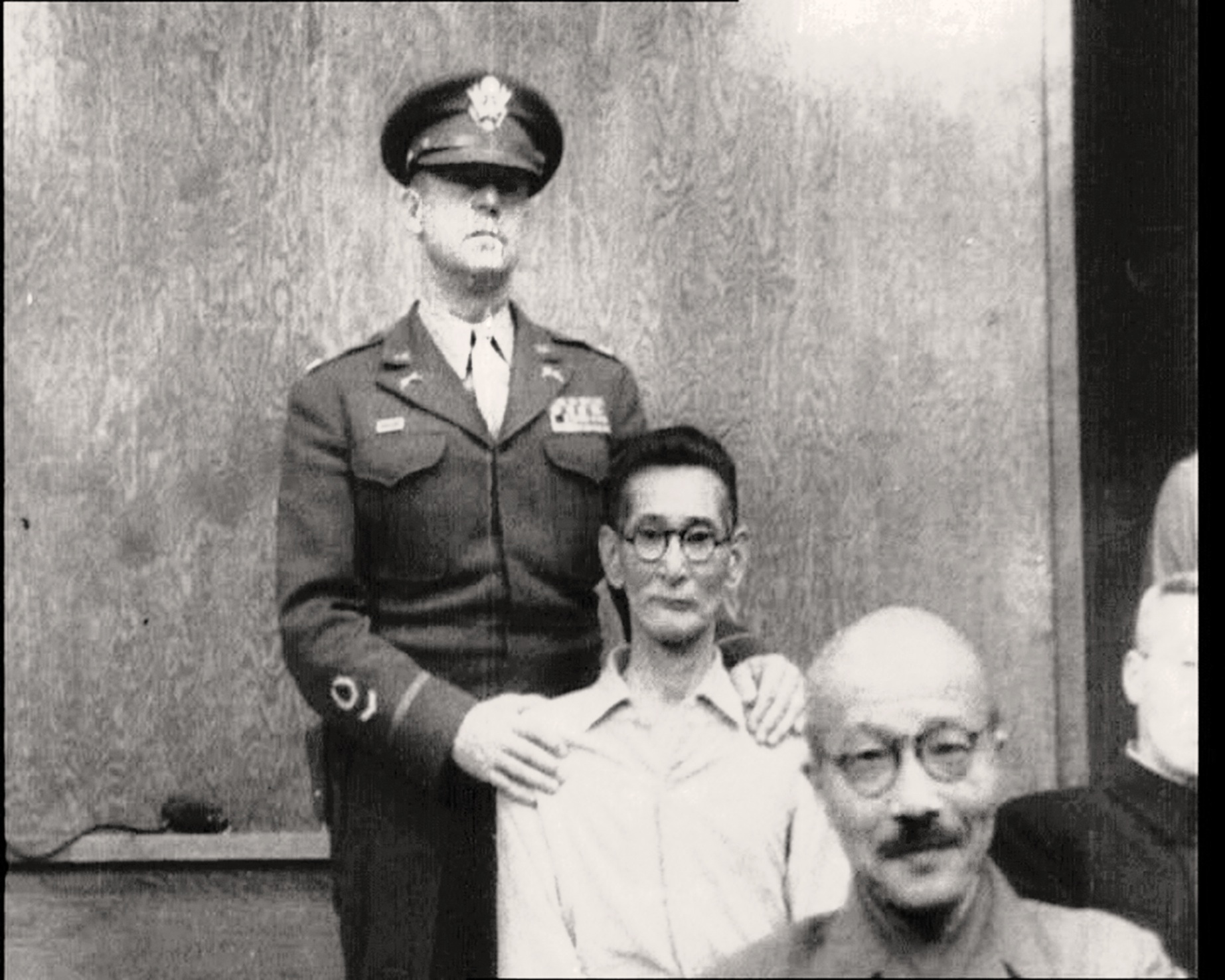

Ōkawa hitting Tojo

illustration {{DEFAULTSORT:Okawa, Shumei 1886 births 1957 deaths 20th-century Japanese historians 20th-century Japanese translators Deaths from asthma Historians of Japan Far-right politics in Japan Japanese anti-capitalists Japanese nationalists Japanese non-fiction writers Japanese fascists Shōwa Statism Hosei University faculty Pan-Asianists People acquitted by reason of insanity People from Yamagata Prefecture People indicted for war crimes Takushoku University faculty Translators of the Quran into Japanese University of Tokyo alumni

Japanese nationalist

is a form of nationalism that asserts the belief that the Japanese are a monolithic nation with a single immutable culture, and promotes the cultural unity of the Japanese. Over the last two centuries, it has encompassed a broad range of ideas a ...

and Pan-Asianist

Satellite photograph of Asia in orthographic projection.

Pan-Asianism (''also known as Asianism or Greater Asianism'') is an ideology aimed at creating a political and economic unity among Asian peoples. Various theories and movements of Pan-Asi ...

writer, known for his publications on Japanese history

The first human inhabitants of the Japanese archipelago have been traced to prehistoric times around 30,000 BC. The Jōmon period, named after its cord-marked pottery, was followed by the Yayoi period in the first millennium BC when new invent ...

, philosophy of religion

Philosophy of religion is "the philosophical examination of the central themes and concepts involved in religious traditions". Philosophical discussions on such topics date from ancient times, and appear in the earliest known texts concerning ph ...

, Indian philosophy

Indian philosophy refers to philosophical traditions of the Indian subcontinent. A traditional Hindu classification divides āstika and nāstika schools of philosophy, depending on one of three alternate criteria: whether it believes the Veda ...

, and colonialism

Colonialism is a practice or policy of control by one people or power over other people or areas, often by establishing colonies and generally with the aim of economic dominance. In the process of colonisation, colonisers may impose their relig ...

.

Background

Ōkawa was born inSakata, Yamagata

is a city located in Yamagata Prefecture, Japan. , the city had an estimated population of 106,244 in 39,320 households, and a population density of 180 people per km2. The total area of the city is .

History

The area of present-day Sakata was ...

, Japan in 1886. He graduated from Tokyo Imperial University

, abbreviated as or UTokyo, is a public research university located in Bunkyō, Tokyo, Japan. Established in 1877, the university was the first Imperial University and is currently a Top Type university of the Top Global University Project by ...

in 1911, where he had studied Vedic

upright=1.2, The Vedas are ancient Sanskrit texts of Hinduism. Above: A page from the '' Atharvaveda''.

The Vedas (, , ) are a large body of religious texts originating in ancient India. Composed in Vedic Sanskrit, the texts constitute the ...

literature and classical Indian philosophy. After graduation, Ōkawa worked for the Imperial Japanese Army General Staff

The , also called the Army General Staff, was one of the two principal agencies charged with overseeing the Imperial Japanese Army.

Role

The was created in April 1872, along with the Navy Ministry, to replace the Ministry of Military Affairs ...

doing translation work. He had a sound knowledge of German, French, English, Sanskrit

Sanskrit (; attributively , ; nominally , , ) is a classical language belonging to the Indo-Aryan branch of the Indo-European languages. It arose in South Asia after its predecessor languages had diffused there from the northwest in the late ...

and Pali

Pali () is a Middle Indo-Aryan liturgical language native to the Indian subcontinent. It is widely studied because it is the language of the Buddhist ''Pāli Canon'' or ''Tipiṭaka'' as well as the sacred language of ''Theravāda'' Buddhism ...

.

He briefly flirted with socialism

Socialism is a left-wing economic philosophy and movement encompassing a range of economic systems characterized by the dominance of social ownership of the means of production as opposed to private ownership. As a term, it describes the e ...

in his college years, but in the summer of 1913 he read a copy of Sir

''Sir'' is a formal honorific address in English for men, derived from Sire in the High Middle Ages. Both are derived from the old French "Sieur" (Lord), brought to England by the French-speaking Normans, and which now exist in French only as ...

Henry Cotton's ''New India, or India in transition'' (1886, revised 1905) which dealt with the contemporary political situation. After reading this book, Ōkawa abandoned "complete cosmopolitanism" (''sekaijin'') for Pan-Asianism. Later that year articles by Anagarika Dharmapala

Anagārika Dharmapāla (Pali: ''Anagārika'', ; Sinhala: Anagārika, lit., si, අනගාරික ධර්මපාල; 17 September 1864 – 29 April 1933) was a Sri Lankan Buddhist revivalist and a writer.

Anagarika Dharmapāla is not ...

and Maulavi Barkatullah

Mohamed Barakatullah Bhopali, known with his honorific as Maulana Barkatullah (7 July 1854 – 20 September 1927), was an Indian revolutionary with sympathy for the Pan-Islamic movement. Barkatullah was born on 7 July 1854 at Itwra Mohall ...

appeared in the magazine ''Michi'', published by Dōkai The is a Japanese new religion founded by Matsumura Kaiseki in 1907 which synthesizes aspects of Christian, Confucian, Daoist, and traditional Japanese thought. Its four main tenets are theism (Japanese: 信神), ethical cultivation (Japanese: � ...

, a religious organization in which Ōkawa was later to play a prominent part. While he studied, he briefly housed the Indian independence leader Rash Behari Bose

Rash Behari Bose (; 25 May 1886 – 21 January 1945) was an Indian revolutionary leader against the British Raj. He was one of the key organisers of the Ghadar Mutiny and founded the First Indian National Army during World War 2. The Indian N ...

.

After years of study of foreign philosophies, he became increasingly convinced that the solution to Japan's pressing social and political problems lay in an alliance with Asian independence movements, a revival of pre-modern Japanese philosophy

Japanese philosophy has historically been a fusion of both indigenous Shinto and continental religions, such as Buddhism, Taoism and Confucianism. Formerly heavily influenced by both Chinese philosophy and Indian philosophy, as with Mitogaku and ...

, and a renewed emphasis on the ''kokutai

is a concept in the Japanese language translatable as " system of government", "sovereignty", "national identity, essence and character", "national polity; body politic; national entity; basis for the Emperor's sovereignty; Japanese constitu ...

'' principles.

In 1918, Ōkawa went to work for the

In 1918, Ōkawa went to work for the South Manchurian Railway

The South Manchuria Railway ( ja, 南満州鉄道, translit=Minamimanshū Tetsudō; ), officially , Mantetsu ( ja, 満鉄, translit=Mantetsu) or Mantie () for short, was a large of the Empire of Japan whose primary function was the operatio ...

Company, under its East Asian Research Bureau. Together with Ikki Kita

was a Japanese author, intellectual and political philosopher who was active in early Shōwa period Japan. Drawing from an eclectic range of influences, Kita was a self-described socialist who has also been described as the "ideological father ...

he founded the nationalist discussion group and political club '' Yūzonsha''. In the 1920s, he became an instructor of history and colonial policy at Takushoku University

Takushoku University (拓殖 大学; ''Takushoku Daigaku'', abbreviated as 拓大 ''Takudai'') is a private university in Tokyo, Japan. It was founded in 1900 by Duke Taro Katsura (1848–1913).

, where he was also active in the creation of anti-capitalist

Anti-capitalism is a political ideology and Political movement, movement encompassing a variety of attitudes and ideas that oppose capitalism. In this sense, anti-capitalists are those who wish to replace capitalism with another type of economi ...

and nationalist student groups. Meanwhile, he introduced Rudolf Steiner

Rudolf Joseph Lorenz Steiner (27 or 25 February 1861 – 30 March 1925) was an Austrian occultist, social reformer, architect, esotericist, and claimed clairvoyant. Steiner gained initial recognition at the end of the nineteenth century as a ...

's theory of social threefolding to Japan. He developed a friendship with Aikido

Aikido ( , , , ) is a modern Japanese martial art that is split into many different styles, including Iwama Ryu, Iwama Shin Shin Aiki Shuren Kai, Shodokan Aikido, Yoshinkan, Renshinkai, Aikikai and Ki Aikido. Aikido is now practiced in around 1 ...

founder Morihei Ueshiba

was a Japanese martial artist and founder of the martial art of aikido. He is often referred to as "the founder" or , "Great Teacher/Old Teacher (old as opposed to ''waka (young) sensei'')".

The son of a landowner from Tanabe, Ueshiba st ...

during this time period.

In 1926, Ōkawa published his most influential work: , which was so popular that it was reprinted 46 times by the end of World War II. Ōkawa also became involved in a number of attempted coups d'état by the Japanese military

The Japan Self-Defense Forces ( ja, 自衛隊, Jieitai; abbreviated JSDF), also informally known as the Japanese Armed Forces, are the unified ''de facto''Since Article 9 of the Japanese Constitution outlaws the formation of armed forces, th ...

in the early 1930s, including the March Incident, for which he was sentenced to five years in prison in 1935. Released after only two years, he briefly re-joined the South Manchurian Railway Company before accepting a post as a professor at Hosei University

is a private university based in Tokyo, Japan.

The university originated in a school of law, Tōkyō Hōgakusha (, i.e. Tokyo association of law), established in 1880, and the following year renamed Tōkyō Hōgakkō (, i.e. Tokyo school of law ...

in 1939. He continued to publish numerous books and articles, helping popularize the idea that a " clash of civilizations" between the East and West was inevitable, and that Japan was destined to assume the mantle of liberator and protector of Asia against the United States and other Western nations.

Tokyo War Crimes Tribunal

After World War II, the

After World War II, the Allies

An alliance is a relationship among people, groups, or states that have joined together for mutual benefit or to achieve some common purpose, whether or not explicit agreement has been worked out among them. Members of an alliance are called ...

prosecuted Ōkawa as a class-A war criminal. Of the twenty-eight people indicted with this charge, he was the only one who was not a military officer or government official. The Allies described him to the press as the "Japanese Goebbels

Paul Joseph Goebbels (; 29 October 1897 – 1 May 1945) was a German Nazi politician who was the ''Gauleiter'' (district leader) of Berlin, chief propagandist for the Nazi Party, and then Reich Minister of Propaganda from 1933 to 19 ...

" and said that he had long agitated for a war between Japan and the West. In pre-trial hearings, Ōkawa said that he had merely translated and commented on Vladimir Solovyov's geopolitical philosophy in 1924, and that in fact Pan-Asianism did not advocate for war.

During the trial, Ōkawa behaved erratically, including dressing in pajamas, sitting barefoot, and slapping the head of former prime minister Hideki Tōjō

Hideki Tojo (, ', December 30, 1884 – December 23, 1948) was a Japanese politician, general of the Imperial Japanese Army (IJA), and convicted war criminal who served as prime minister of Japan and president of the Imperial Rule Assista ...

while shouting "Inder! Kommen Sie!" (Come, Indian!) in German. From the beginning of the tribunal, Ōkawa was saying that the court was a farce and not even worthy of being called a legal court. He was also heard to shout "This is act one of the comedy!" U.S. Army

The United States Army (USA) is the land service branch of the United States Armed Forces. It is one of the eight U.S. uniformed services, and is designated as the Army of the United States in the U.S. Constitution.Article II, section 2, cl ...

psychiatrist Daniel Jaffe examined him and reported that he was unfit to stand trial. The presiding judge Sir William Webb concluded that he was mentally ill and dropped the case against him. Some believed that he was feigning madness. Of the remaining defendants, seven were hanged and the rest imprisoned. (review of book by Eric Jaffe)

After the war

Ōkawa was transferred from the jail to a US Army hospital in Japan, which confirmed mental illness caused bysyphilis

Syphilis () is a sexually transmitted infection caused by the bacterium ''Treponema pallidum'' subspecies ''pallidum''. The signs and symptoms of syphilis vary depending in which of the four stages it presents (primary, secondary, latent, an ...

. Later, he was transferred to Tokyo Metropolitan Matsuzawa Hospital

is a public, 1,264-bed psychiatric hospital in Setagaya, Tokyo, Japan. It was founded in 1879. It is a hospital established and operated by the Tokyo Metropolitan Government, and is a general hospital equipped with other clinical departments as w ...

, a mental hospital, where he completed the third Japanese translation of the entire Quran

The Quran (, ; Standard Arabic: , Classical Arabic, Quranic Arabic: , , 'the recitation'), also romanized Qur'an or Koran, is the central religious text of Islam, believed by Muslims to be a revelation in Islam, revelation from God in Islam, ...

. He was released from hospital in 1948, shortly after the end of the trial. He spent the final years of his life writing a memoir, ''Anraku no Mon'', reflecting on how he found peace in the mental hospital.

In October 1957, Prime Minister of India

The prime minister of India (IAST: ) is the head of government of the Republic of India. Executive authority is vested in the prime minister and their chosen Council of Ministers, despite the president of India being the nominal head of the ...

Jawaharlal Nehru

Pandit Jawaharlal Nehru (; ; ; 14 November 1889 – 27 May 1964) was an Indian anti-colonial nationalist, secular humanist, social democrat—

*

*

*

* and author who was a central figure in India during the middle of the 20t ...

requested an audience with him during a brief visit to Japan. The invitation was hand-delivered to Ōkawa's house by an Indian Embassy official, who found that Ōkawa was already on his deathbed and was unable to leave the house. He died on 24 December 1957.Sekioka Hideyuki. ''Ōkawa Shūmei no Dai-Ajia-Shugi''. Tokyo: Kodansha

is a Japanese privately-held publishing company headquartered in Bunkyō, Tokyo. Kodansha is the largest Japanese publishing company, and it produces the manga magazines ''Nakayoshi'', ''Afternoon'', ''Evening'', ''Weekly Shōnen Magazine'' an ...

, 2007. p. 203.

Major publications

* Some issues in re-emerging Asia (復興亜細亜の諸問題), 1922 * A study of the Japanese spirit (日本精神研究), 1924 * A study of chartered colonisation companies (特許植民会社制度研究), 1927 * National History (国史読本), 1931 * 2600 years of the Japanese history (日本二千六百年史), 1939 * History of Anglo-American Aggression in East Asia (米英東亜侵略史), 1941 :* Best-seller in Japan during WW2 * Introduction to Islam (回教概論), 1942 * Quran (Japanese translation), 1950Notes

References

* * * * * * *Further reading

* *External links

Ōkawa hitting Tojo

illustration {{DEFAULTSORT:Okawa, Shumei 1886 births 1957 deaths 20th-century Japanese historians 20th-century Japanese translators Deaths from asthma Historians of Japan Far-right politics in Japan Japanese anti-capitalists Japanese nationalists Japanese non-fiction writers Japanese fascists Shōwa Statism Hosei University faculty Pan-Asianists People acquitted by reason of insanity People from Yamagata Prefecture People indicted for war crimes Takushoku University faculty Translators of the Quran into Japanese University of Tokyo alumni